A Talk With Mr. Rios About The Importance of Teaching the 1921 Tulsa Massacre

During the summer of 1921 in what is arguably the most atrocious act of racial violence plagued Tulsa, Oklahoma from May 31st to June 1st in an 18-hour period. During the time, there was a rise in racial tension that was caused when one allegation from Sarah Page, a white woman, against a black man named Dick Rowland allowed a white mob to form and tear the prosperous Black neighborhood in Tulsa that was the Greenwood District.

It’s strange to me that I haven’t been taught about this in school. Although I have a few more years for that to change, at this point in my academic career I’ve had units about various other massacres like the Boston Massacre in 1770, or the Reading Railroad Massacre of 1877. An estimated 10-16 people died in West Virginia during the Reading Railroad Massacre with double the amount that were injured. Boston resulted in 5 deaths. The race-based massacre that is Tulsa 1921 saw as many as 300 dead with nearly three times that injured. This doesn’t even include the hundreds more who were then without a home or any sort of safe place to be.

I don’t bring these numbers up to undermine any event important to history. I bring these numbers up to emphasize how strange it is that what has been called one of the nation’s worst incidents of racial violence has only recently started being taught in schools. Up until 2020, the single worst incident of racial violence in America wasn’t even required to be taught.

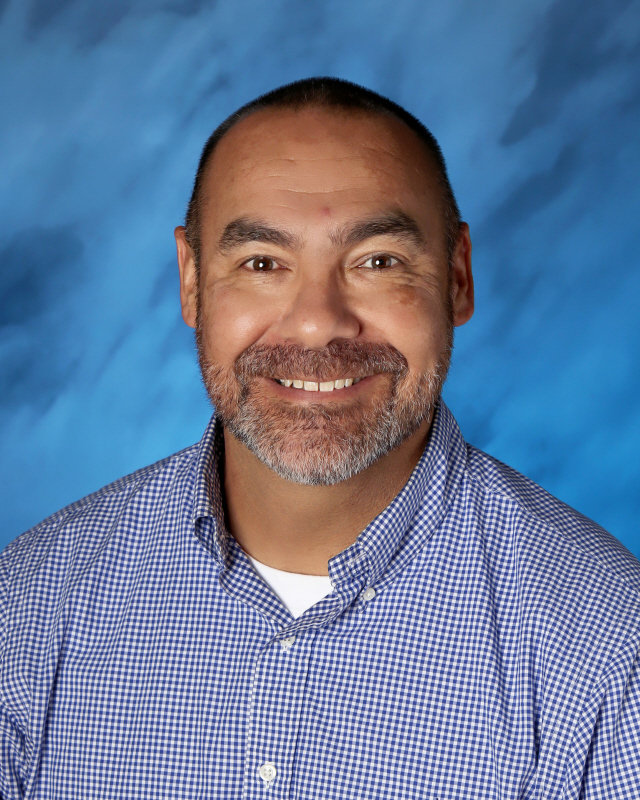

I spoke with AP U.S. History and AP Psychology teacher Mr. Rios about Tulsa’s representation in the school curriculum. Our conversation developed into a discussion about the equal opportunity seen at our school.

What do you know about the Tulsa Massacre?

I know quite a bit about [Tulsa], and we’re just about to the part in AP US History class where we are shifting from getting involved in WWI. Getting involved in WWI is gonna kinda lead us to that great migration, up north. We also previously have talked about the group of African Americans we call the “exodusters” who left parts of the south, [and] going to Kansas because they were kinda told and thought that might be where they’d be able to get land and they took advantage of some of the homestead act land up there in the area of Kansas. So we’re talking about the movement of African Americans slowly but surely out of the South at this period.

We look at Oklahoma as not necessarily the traditional south because it has been labeled as Indian territory for so long. But in the last unit, we talked about the Oklahoma land rush, the Sooners, and the groups coming over and claiming all this land. When we get to the 20’s we’ll talk about [how] we’ve had this great migration, and because of this great migration we have areas like Harlem, and the Harlem Renaissance.

We’ll talk about Chicago and a number of the race riots that happened in Chicago as African Americans moved from the South to the North and took some of those jobs that were available because immigration was basically shut off during WWI. We’ll talk about the successes of that but then we’ll also bring in, we just read about Woodrow Wilson’s administration.

We just wrote a document about Woodrow Wilson’s administration and how it basically increased the segregation within the federal government. The reading that we read talked about we have some areas of the government where you have black men being managers over white women and how “that’s not a good thing so we need to segregate them”, so we’ve already taught kind of about this idea that because this ties into the whole thing that kicks off Tulsa is that accusation of a white woman being raped by a black man. We’ve kind of already done that part already so once we move into the Harlem renaissance and the growth there. I’ll talk about Chicago, but then I’ll also move down to Tulsa.

In our AP US History [class], we have a document reader that has primary and secondary source documents. We try to fill this oftentimes with primary source documents and secondary source documents that highlight parts of history that aren’t really well covered in a textbook. Moving into that period, we specifically added some documents dealing with Tulsa.

One specific document dealing with Tulsa’s impact in that region. We [also] have a bunch of stuff on the Klan in Denver.

I didn’t know they had a big presence in Denver.

Rios: Huge presence in Denver. The mayor and the governor were both Klansmen.

We’ll go through the long lasting legacy of the great migration, and then we have this guy Buck Colbert Franklin [who] eye witnessed May 31st, 1921 (start of the Tulsa massacre) [and] his word for word depiction of that. You have these greater areas of opportunity for African Americans in places where we see the urban centers like Harlem with the growth there and the flowering of African American culture while at the same time existing in a society where basically much of their progress was stilted by racism. That’s how we’ll approach it as we talk about that period.

We’ll go from talking about the changing society from Marcus Garvey, African-Americans, and the Harlem renaissance. Then there will be a new slide inserted dealing specifically with the aspects of Tulsa and what happened as an action. This whole lecture I do here is talked about as action and reaction. As we start to see things changing in the 20’s and As more freedom is fought for and provided, you’re gonna have the reaction of people who don’t like that change.

We talk about that all year long in history. In my history [class], we talk about this idea of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. We’re all created equal. When that’s said in 1776, I look at it with my class as a goal. We weren’t there in 1776, [and] you can argue we’re not there now, but as long as it’s a continual progression towards that, we’ll build that all year long as various different groups get various different rights as we talk about the growth of the country. So that’s how I usually approach Tulsa.

How do you feel about how it’s implemented into the curriculum?

Rios: People who are my age, and I’m 50 years old, when we went to college and high school, a lot of things we are now highlighting probably weren’t highlighted in the curriculum. As we move forward and look at different things and different aspects and who’s writing the history, the AP curriculum, [and] this course guide, they’ve done a lot better job of incorporating “hey let’s look at the history of some of these groups that have been marginalized that we haven’t focused on before”, so AP’s made that a focus.

We’ve made it a focus in our department as we’ve gone through our training about culturally relevant education in how important it is for marginalized groups to see representation of themselves in a classroom in a positive light. We’ll look through our units and say “this is a unit where we don’t have a lot of representation of marginalized groups,” and then we will as a group “what are some things we can add to this?”.

We do a different one of these every year, and if we realize there’s not a reading on this group of people in this period, let’s find something that’s historically based, and let’s put it in there. If they’re reading out of a textbook they’re not gonna get it, but if we’re talking about it in class they’re gonna get it there. It’s an important piece of the puzzle to represent groups. Tulsa as a specific event is a very good example of having black communities flourish.

Today, if you were in your advisory class, they did the Black History Month lesson on 5 points. Same basic thing, African Americans were locked into this 5 point area because of what was called redlining, and they were thriving. But then as time went on, because of various different issues and aspects, that community fell apart.

We look at Tulsa and that community was basically destroyed by this group. Overtime, they’ve tried to reinvigorate certain parts, but it hasn’t been that successful. You look at different things as you talk about the concept of eminent domain as Tulsa got bigger and started spreading out.

The white communities had advantages over the black communities. Unless you could move into one of those communities you were probably locked out of moving forward in certain areas. I would say to each teacher, we talk about them as being the professional in the classroom. In this case with Tulsa, we give them state standards that they’re supposed to be adhering to. They are in PLC, or professional learning communities, where we talk about the essentials we’re covering.

Within that realm they then have freedom to go deeper into various different issues. You might have a teacher who’s really engaged in Tulsa and wants to bring that up. They might do a more thorough job than another teacher who’s gonna focus on the Harlem renaissance and the growth there. It’s not necessarily equal in every single class, but I think the minority perspective is being more and more integrated into the curriculum definitely since I’ve been here.

How do you feel Tulsa impacts us today?

Rios: If you’re watching the news, if you’re watching various channels on television, you consistently hear a drum of racial tension. My perspective is, I look at the news media, oftentimes it’s more about how many people they’ve got watching, and “how we get them to watch?”. “Well let’s make something as dramatic as possible”.

I’m not saying there aren’t racial issues, but very rarely do you see the stories of groups of different ethnicities working together. These groups succeed, being successful, and what’s making them successful. More often than not you will see opposing views on various different channels depending on what their political view or political perspective is. When we look back at Tulsa, we can look back at what and why it happened.

If we put things in place to stop that from happening again, we’ve made progress. But I also think it’s a good learning experience to understand this did take place, in reality a hundred years ago, but historically speaking, not all that long ago. We still look at issues with disparities we see within communities today.

Oftentimes those discussions you see on TV are extremely one sided. You don’t necessarily get a full perspective and debate about it. It’s more simply because “there’s racism there”. If the only answer you say is “there’s racism there”, then the only fix is we gotta eradicate racism. How exactly do you do that?

You can try to do it through various legislation. But again, to really change somebody’s heart if they have racism in the heart, is a much more difficult thing to do than just have some politicians kinda grand stand and try to get some piece of legislation signed. I think a lot of politicians are more concerned with getting elected and looking good to their constituents, and “let me throw this bill up there because it shows that I’m tough on racism”, but not really considering the impacts that that bill could have, positive and/or negative.

I think that it’s an important thing to look back at something in history and really try to learn what are the lessons we can learn from Tulsa. This was a community that was thriving with African-Americans who were being successful in their community and thriving, and yet it was allowed to be destroyed because of an accusation of a man in an elevator. A black man and a white woman.

You would hope that, not saying that there aren’t obviously incidences of racism today, that something on that scale would not be possible today. An event like this if we have a flourishing black community and there’s some accusation and you have a mob of men coming to try to destroy. I think you’d probably see that black community fight back in a way that the black community in Tulsa wasn’t equipped to and doesn’t feel like they could at that time.

I have some documents in there that show in the 20’s, Klansmen marching down the street in D.C. Now do they have the right to do that today? Yes, they do the right to do that right. You’d probably see a lot more violent reaction to that today then you did in the 20’s. I think that if you just listen to some of the rhetoric today you would feel like we’re in a much worse place racially than we’ve ever been. But if you read different black voices, then maybe just some of the ones that are on TV, you hear.

One of the people I really like to listen to and I really respect is former Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice. Condoleezza Rice grew up in Alabama. Condoleezza Rice knew one or two of the girls who were killed in the Alabama Church Bombing. She grew up in that community. She grew up understanding racism. She looks at some within politics today who try to argue that things are worse today than they were back then, and she thinks it’s just nonsensical if you can’t look at the advancements, the opportunities that we’ve been given.

I look at our community here at Grandview [and] I look at all the resources that are provided for students to help support them, yet some students aren’t accessing those for whatever reason. I look at myself, being a Hispanic male growing up in a community that was predominantly white, and did I look like most of the other kids? No. Did my parents have a college education like most of the other kids? No. But I was in school thinking, “my dad and mom worked their tails off to get me into this good school district, I’m gonna work my tail off to show them I’m grateful for putting me into this environment,” because the environment I moved from was not a very academically driven environment.

Most of the kids I was born around didn’t go on to barely graduate high school, [and] maybe didn’t go onto college. Some got involved in gangs and so on. Whereas my parents moved me into a more middle-class community, and I took a different path. The students who are here, are in a school, in a school district, that is fighting to help them be successful, but it can’t happen if they’re not a participant in that.

Do you feel like they’re accepting that fight?

Rios: I feel some might be, but I think some aren’t. That’s where we get back to a point that I like about personal accountability. Is life fair? No, life’s not fair. It’s fine. But what are you doing with the opportunities you are being given?

Regardless if you’re black, you’re brown, you’re Asian, if you’re Indian. Whatever race, ethnicity, nationality, religion you are, I feel this school district, and our school in particular, I look at the vast amount of opportunities that are here.

I look at teachers, who are spending a ton of time working with students who are willing and get that help. I truly believe if a student really wants that help, and is willing to work hard for it, they can be successful here. Regardless of where they’re at currently or if they feel like they’re disadvantaged in some way, I personally think we’re working really hard to try to provide an equal opportunity.

Hello! I’m Bradley and this is my junior year at Grandview and my third year on The Chronicle Staff. I am the Photo Galleries Manager. My favorite Chronicle...

![Bill HB24-1448: What Does It Mean? [OPINION]](https://ghschronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Hayne-Photo-1-600x450.png)

![Colorado Rockies: No Trophy in Sight [Opinions]](https://ghschronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IMG_3018-2-600x450.jpg)

![Freshman 101: Great Intentions; Repetitive Practices [Opinions]](https://ghschronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Screen-Shot-2024-05-02-at-1.58.44-PM-600x492.png)