In defense of: “I was born in the wrong generation girls”

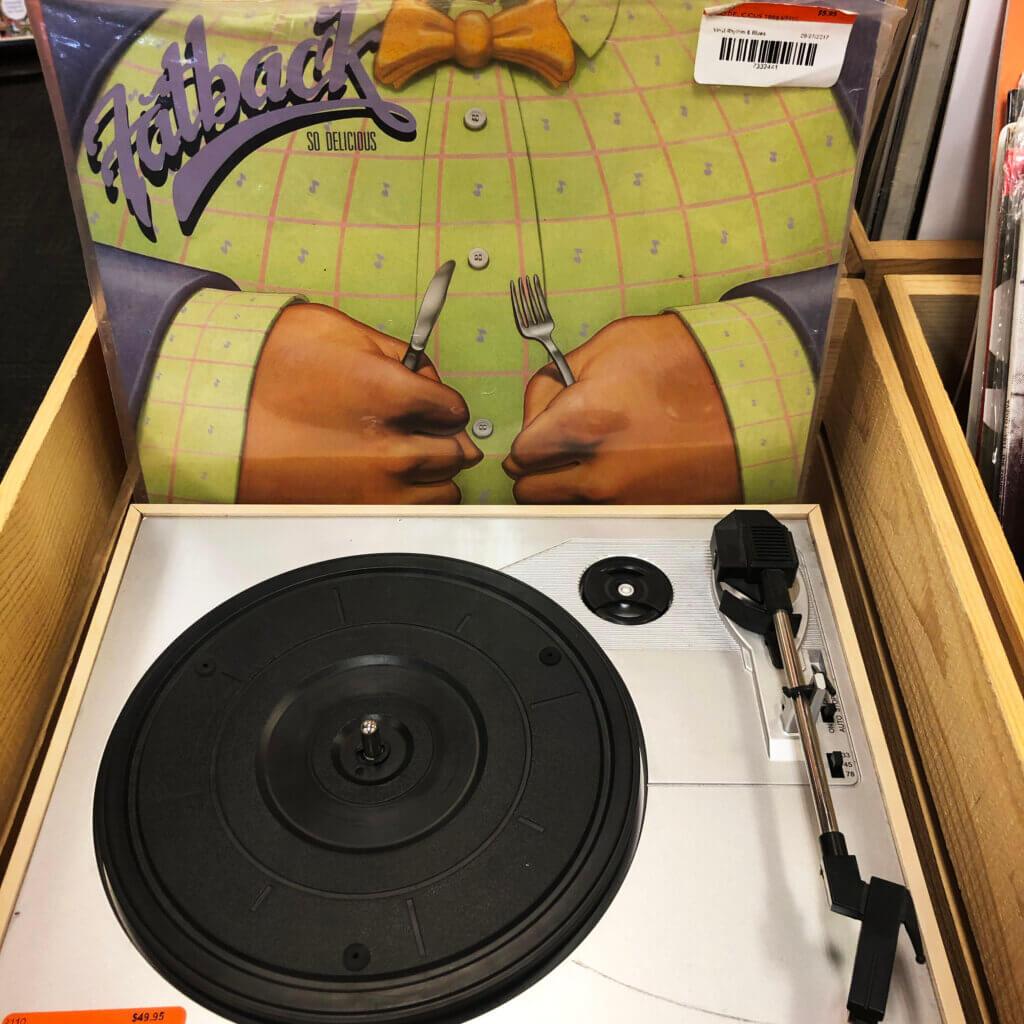

We all know one. They have a record player in their room, mom jeans and vintage clothes (which they say are thrifted but are definitely from Urban Outfitters), they read old books, watch old movies and constantly let out big sighs and claim, “I was just born too late.”

Ah yes, the woes of being born in a generation with portable pocket computers, access to any entertainment at any time, high fructose corn syrup, and 50 different kinds of chips to choose from at the grocery store.

And yet sometimes I just want to be a punk rocker with flowers in my hair, not a depressed anxious member of Gen Z. Disregarding the fact that I should have no reason to be depressed or anxious as a white middle class suburban Denver Gen Z-er, and that the aesthetics of the 60s and other past decades isn’t worth the sexism, racism and lesser standard of living.

But I am able to understand Millenials and Gen Z’s obsession with previous decades.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the United States became more and more industrialized and urbanized. For the first time, more than 50% of the U.S. population were no longer self-subsistent and had cheap access to textiles and food ect. As time continued, people left the farms, and moved into cities as farmers who stayed behind were able to mass produce crops.

During the major shift to suburbanization in the 1950s the usage of plastics and the creation of fast food chains became rampant. This decade marked the beginning of the United States’ exponential rate of “throw away culture.” Or rather the culture of a saturated market from the over-production of commodities, that is far beyond what is necessary to survive off of, and to an extent that has convinced us that it is not only necessary to have 50 different kinds of chips to choose from but is vital for “the restoration of our freedom.”

Today with streaming apps such as Spotify, Netflix, YouTube, Amazon, Kindle, ect., we are able to go through music and movies and books like plastic spoons and plates, binging TV for hours on end, disposing of it once we are done, and clicking on the next video, song, or episode.

We even do this in dating, scrolling through hundreds of people on dating apps and simply swiping left or right solely on initial appearances.

In the 16th century, royalty and aristocrats would show off their wealth by eating a slice of pineapple or a piece of chocolate. But in 2020, even low income people can enjoy their “morning chocolate” like Monseigneur the Marquis Evremonde for just a couple dollars.

We are literally living like kings for just $2.99.

Except now our morning chocolate is fraught with chemicals and sugar that are slowly killing us by causing cancer and other diseases that require an abundance of medicine to stagnate our inevitable slow and calculated death.

I believe we are nostalgic based on two things: to escape throw away culture and because we crave a time when we had a distinct monoculture and community.

After the 90s and early 2000s, the unity of a monoculture began to diminish.

Think: what defined 2010s? What will define 2020s?

People born in 2003 and before might be the last generation to experience monoculture, and even for us our monoculture was technology based. We had Disney Channel and Nickelodeon classics, we all lived through the relatable cringy beginnings of social media. This overall defined our adolescence.

However, today’s kids will grow up with the latest and newest technology from the second they exit the womb–which is honestly terrifying because I thought early Gen Z’s attention span and technology addiction was bad enough.

They’ll have all the unlimited TV shows and movies they want, isolating them in pop culture. Whereas we had to wait for the next episode of iCarly or Spongebob to come out and could only watch the amount of movies that we had on DVD.

Humans have always longed for the good old days. We even have presidents using this “nostalgia” as a platform for their campaigns.

And consumer and pop culture industries today have grasped this and amplified it as the neo nostalgia brand: our nostalgia for times we have never lived in is profitable.

To illustrate, one of my favorite T.V./book series is Anne with an E. Anne With an E is set in the 19th century in the Prince Edward Islands. No part of me actually wants to live in the 1800s– let alone Canada during the 1800s– and the show doesn’t make me want to live during that time either. It was an era where people were destined to die if they caught practically any sickness; where there was little plumbing and heating and air conditioner; where black people were oppressed; where women don’t have the right to vote.

2020, materially, is the best time to ever live. All our basic needs are met more than ever in the first world, but it also often feels like the most lonely and divided time. This is why we love past decades and period dramas: for their simplicity in life and culture, where there’s no phones or tests or need to sell your soul for college.

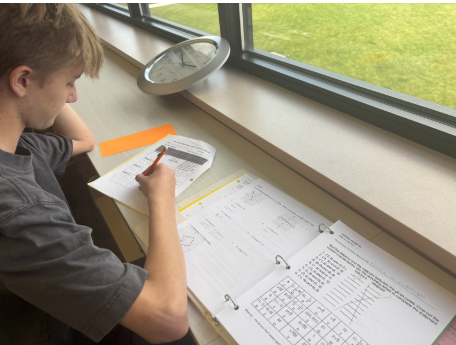

In many ways our contemporary suburban middle class society is run like a business. Growing up on social media, we essentially have to sell ourselves by our profiles, by documenting our lives in order to make friends or get into relationships, or to get a job, or to even just get into a school.

The school system itself operates like a business where we are simply reduced to never ending data and numbers like we never were before. The numbers predict our futures like it’s a business risk or investment. No longer is anything “just for fun.”

I believe one of the biggest contributing factors to our nostalgia of the past—despite our wonderful privileged lives—is that we want to live like a kid not a business.

Of course the entertainment industry romanticizes and inaccurately describes the past and high schoolers lives, it does still depict the simplicity of lives (middle class and white) before the 2000s.

My parents describe it as a different culture. They explain to me that when they were growing up, kids could go and hang out at the park all day or go to the mall or record stores without the constant need to feel like you need to plan it or convince your parents. Yes, there were still places and times they knew they shouldn’t be out, but there was no fear or worry. They had no phones on them, no Life360 or extravagant home security systems, because people looked out for each other. People knew the names of everyone in their neighborhood and to be honest, I don’t even know the name of the person who sits next to me in math class.

Overall, nostalgia makes people feel loved and valued. Nostalgia allows you to feign social support when you are lonely. When we experience nostalgia we generally feel happier, feel closer in our relationships, and feel that life has more meaning–even if it’s for times we have never lived in.

![A Vest Won’t Protect You [OPINION]](https://ghschronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/KoltonZuckerVestPosterOffWhite-450x600.png)

![Executive Order: Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling [OPINION]](https://ghschronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-23-at-2.51.41 PM-600x337.png)